The missing link in the agentic AI value chain

Credit to ChatGPT, obviously

With so many exciting agentic AI startups reaching 3, 5 or even $10 million in ARR in their first year, a question me and my team and Systemiq Capital often find ourselves asking is “what does this company need in order to 10x or 100x?”, or put it another way “what will be the bottleneck to their future growth?”.

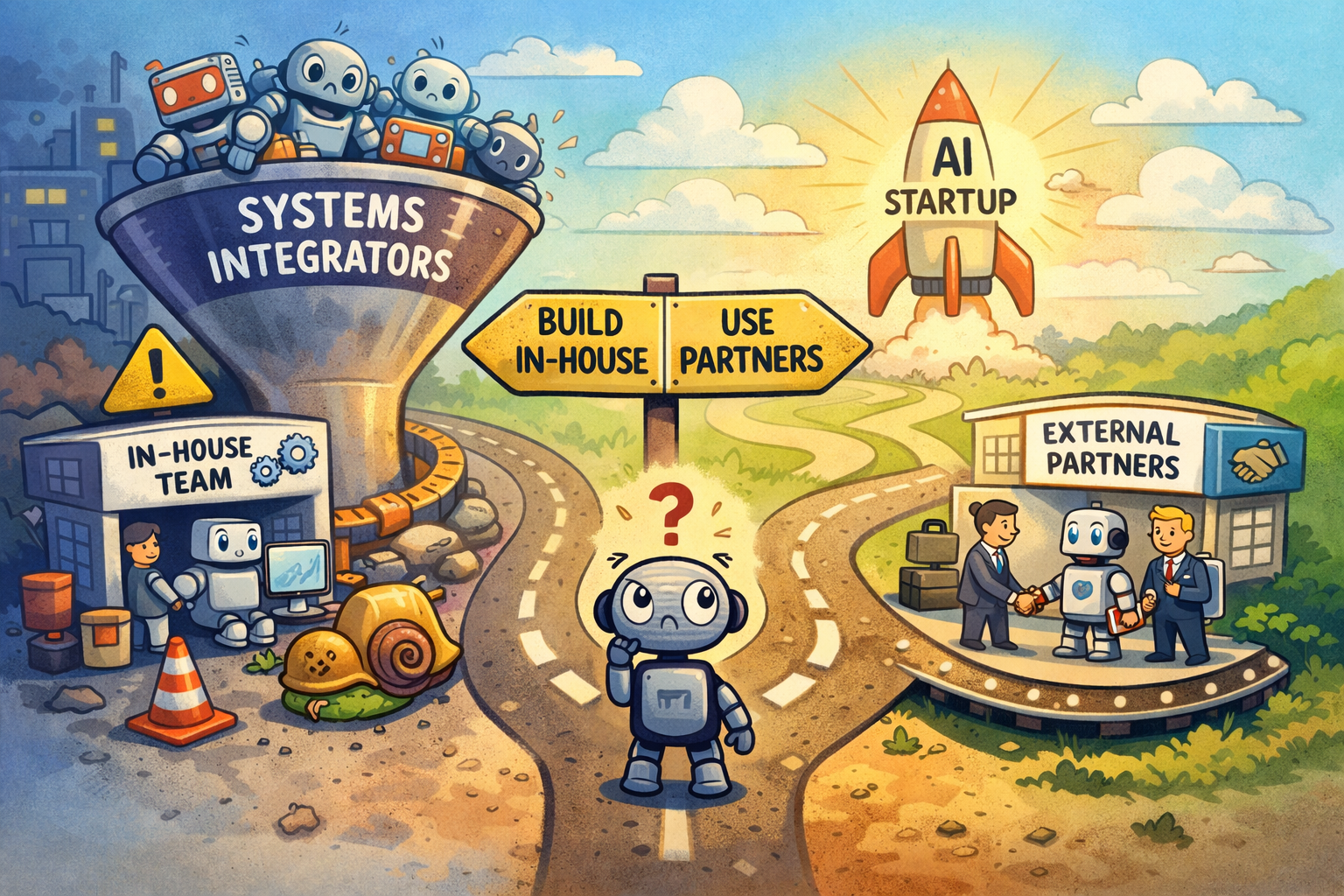

Some of the fastest-growing companies in history, like Cursor or Harvey or Lovable, have yet to show any sign of slowing down. But within our SysCap investment focus, which is where this AI toolbox gets applied to physical industries like manufacturing, logistics, or construction (and as opposed to purely digital- or knowledge-based like coding or legal), we feel like there’s an important ingredient that is not being produced at the desired rate and risks becoming the limiting factor for the growth of the whole ecosystem: systems integrators. I know, I know, it’s not the sexiest topic to read about, but hear me out.

Looking under the hood and into the unit economics of this new crop of Applied AI innovators, a pattern has started to emerge: high-friction deployment of solutions on customers’ systems. Outside of a handful of knowledge-based industries where product-led growth works incredibly well (mainly coding and legal), in areas where we look to invest, i.e. where AI is applied to physical industries, we tend to see quite large gaps between contracted and live revenue, and longer timelines to activate revenue. This indicates some level of friction to deploy, usually either integrating with their legacy tools (e.g. CRM, ERP, IT stack in general) or some level of customization required for the ROI to be compelling to the buyer. In enterprise settings, it’s also typically compounded by sluggish decision-making.

This needn’t be a problem for you, the savvy early-stage founder: you can initially hire a bunch of smart “forward deployment engineers” (AKA the “solutions” team), and put them to work customising the agent to each customer’s particular context. Given that you have to live up to the claim of seamless AI agent deployment, you likely can’t bill your customer for large implementation fees, so it will erode your margins, but your Seed/Series A VC investors probably only care about topline growth anyway, so that’s fine for now.

No, the way I see it, the real issue is what happens when your business truly starts to scale: when you get into the $10-100m ARR range. Assuming unit economics start to matter at some point to later-stage investors, which it will once the hype matures, one of three things need to happen:

Option 1: Your ARR growth decouples from the amount of integration work required, as you have already seen most possible configurations and have allowed the agent to learn from them, minimising the amount of human input required. Gross margins go back up, customer retention stays high, bob’s your uncle. This is by far the most prevalent narrative I hear from founders. I’m very open to it, provided that:

You don’t need to go up-market as you grow: if you go from SMEs to enterprise during that phase, the complexity will likely grow faster than planned, and that might trip up your growth rate.

The implementation work is mainly technical: any human training, workflow discovery, or change management component will be the de facto asymptote for the services intensity in your revenue mix.

There are no intangibles provided by the human “solutions” team that your customers value separately from the pure ROI calculation on the product. This could be trust, or neutrality from internal politics during deployment, or simply emotional intelligence when some middle managers start to freak out about their job security.

Option 2: Your professional services arm grows roughly linearly with your ARR, because product surface area grows at least as fast as it learns the possible deployment configurations. Now that’s concerning, because once your hypergrowth phase tapers off, the market might start to see you as a tech company with sub-par profitability, or something much worse (from the point of view of VCs): a services company…

We see many companies aiming to build the “Palantir of …”, which is meant to show that the chunky services component in the revenue is a feature, not a bug, and that they can build a venture-scale business with gross margins in the mid 60s. Unless you’re going after defence customers with extreme stickiness, you’re honestly not likely to be Palantir comp (is your name even in the Silmarillion?), and anyway it took them 14 years from Series A to IPO, which is not what you want in the blitz-scaling agentic age.Option 3: You outsource all that solutions work to the systems integrator ecosystem. After all, that’s what Accenture and their smaller friends are for, right? This pathway allows your team to remain a lean and mean machine focusing ruthlessly on product quality. My guess is that 5 years from now, this will be the base case for most players in the AI transformation space, in particular for the enterprise segment and the most complex industries (e.g. construction, healthcare, etc.) where customers are least able to make use of turn-key solutions. The little snag is speed: you’re growing ARR at >5x or even >10x a year, and your product is gaining new superpowers on a quarterly basis with each release of the LLM that underpin your architecture. Incumbents can’t keep up with that! They’re used to deploying SAP, which changes architecture only once a decade.

This leads me to the conclusion that, to support the Cambrian explosion of venture-backed agentic startups, we need a similar Cambrian explosion of a new type of systems integrators, built for the agentic age. In “picks and shovels” Far West terminology, these companies will be the ones renting you a string of mules to bring your loot back to town.

The YC seems to agree, having openly called for AI-native agencies to join the Spring 2026 cohort, going against a pretty strongly-held bias by VCs against investing in agencies. The biggest players in the AI ecosystem, from NVIDIA to the hyperscalers, are also all hiring Solutions Architects to help their customers roll out the new models.

I haven’t seen such a blossoming of new integrators yet, I suspect partly because most entrepreneurs think it’s more exciting to try and build a 10-person unicorn than a services company. But when all is said and done, the savvy integrators might do very well, and maybe better risk-weighted than the agentic startups, as I can totally see Accenture or Deloitte acqui-hiring their way into this business (like they did with Faculty AI last month) within 3-5 years when they realise it requires a different culture and more agile workflows than the one they have built in the past 50 years. As a bonus, I hear that these incumbents are currently culling the herd and freezing new hires, so as a new entrant you can fish for cheap in their traditional talent pool of freshly minted graduates!

At the end of the day, as with so many things in venture, it comes down to the team and culture that the founders put in place: the more customer-centric you are, the more likely you’ll be to internalise the integration work, at the risk of bloating your organisation. On the other end of the spectrum, the more product-led you are, the more likely you’ll be to work with external partners to deal with non-core features and integrations, and maybe leaving some money on the table in the process. In any case, in the long-run picking and trusting the best distribution partners could be a cornerstone of your competitive advantage, especially in a space where tech moats can erode faster than sandcastles in a rising tide.

As a founder, how are you thinking about your distribution strategy, how are you trading off gross margin, revenue stickiness, and sales cycles? I’d love to hear your thoughts. I’d especially value your input if you strongly disagree with anything I’ve written here! I’m in the business of “strong bias held lightly”, so please help me forge better ones.